Mum, where do digital pianos come from?

Digital is everywhere. Many everyday devices have become exclusively digital in the past decades. Will the digital piano replace the acoustic piano in the same way? Of course not! The acoustic piano is and will remain "the one and only". So why are there digital pianos, how did they originate and evolve? In this article, you will read all about it!

Today, the digital piano is a good complement or alternative to the acoustic piano. But this has certainly not always been the case. How did the digital piano emerge and evolve?

Two aspects of the piano have been pernicious in the emergence and evolution of an electric and later digital equivalent: First: the piano is indispensable wherever musical entertainment is required, but is not easily transported. It is an instrument for classical music, but also for jazz, pop, etc. But... The instrument does not come with the pianist, the pianist comes to the instrument. The pianist sometimes ended up with a well-maintained and tuned instrument, but just as often with an out-of-tune and poorly maintained antique instrument. Entertainment pianists started yearning for a mobile instrument of their own.

Second: the piano sound is technically/physically/mathematically one of the most complex sounds there is... The tonal range (from the lowest to the highest note that can be produced) is enormous! (Second largest of all musical instruments. Only some church organs have a larger range). The timbre (harmonic content of the sound) is enormously complex, and not only different for each key, the harmonic content also varies in an infinite number of ways, depending on the hardness of the touch, the intonation and adjustment, and the playing style of the pianist. This complexity has ensured that it took almost 100 years before there was an "acceptable" electric/electronic alternative to the acoustic piano. And this complexity also means that today, the "true enthusiast" still chooses an acoustic piano. To understand the story of the digital piano, we need to take a closer look at three parallel evolutions: the evolution of the electro-acoustic piano, the evolution of the synthesiser, and the evolution of the "sampling" technique.

Let's go back to the 1930s. With the rise of jazz and especially the Big Bands, an essential problem arose: the Big Bands toured the United States with their whole set, preferably carrying their own piano everywhere. Since the numerous horns could produce quite a lot of decibels, the pianist preferred to have a grand piano as large as possible, in order to achieve a similar sound level. This was in stark contrast to the requirements of the logistics manager of such a tour: he wanted a piano as small as possible, light and easy to transport. Bechstein and Siemens already anticipated this demand. In 1929, they put an electro-acoustic piano on the market: a short acoustic grand piano, in which "microphones" (actually more like "recording magnets") under the strings could capture the sound and, after amplification, project it into the hall via loudspeakers. This "Neo-Bechstein" (as the instrument was officially called) was (too) far ahead of its time. Petrof turned it into the neo-Petrof, and the American company Story & Clarck also put a similar instrument on the market. The idea was brilliant, but the technology was not yet advanced enough. However the message was clear: in addition to our acoustic grand piano, we need an alternative that offers a solution in specific cases.

It took until the 1950s before a more workable solution was found, based on partly the same idea. With the rise of pop and rock music, the need for a piano that was easy to transport and easy to amplify became even greater. The Fender Rhodes and the Wurlitzer piano saw the light of day. Although, piano? These instruments actually didn't sound like an acoustic piano at all! (In the case of the Fender Rhodes, real piano mallets struck metal rods, which were then amplified via a pick-up, just like an electric guitar. The Wurlitzer had metal reeds). Despite the fact that the advantages did not outweigh the different sound, many pianists bought this instrument. Even today, the typical sound can be found in pop and jazz music, and there are pianists actively looking for an original Rhodes or Wurlitzer piano.

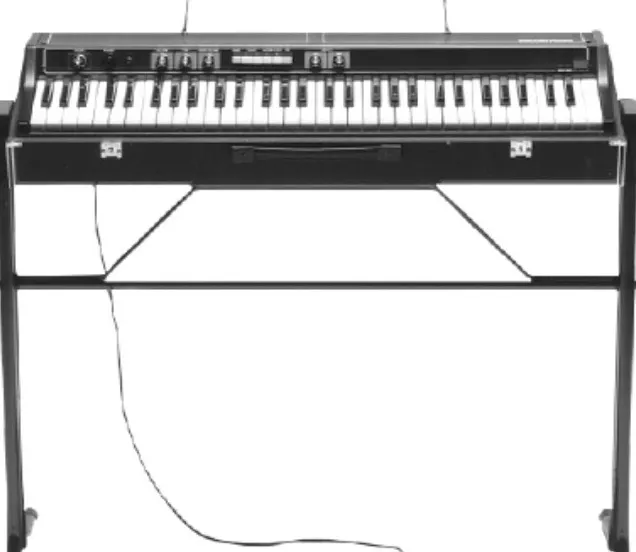

It was not until the 1970s that the identical principle of the Neo-Bechstein was revived. Yamaha then set a new standard in electro-acoustic pianos with, among others, the CP70/CP80: An acoustic piano with real strings, but very short and without a soundboard. The vibrations of the strings were amplified with pick-ups (microphones). The typical sound can be found in many pop recordings from that period. Just think of all the music by ABBA. However this instrument remained too heavy and expensive for many.

Alongside the rise of electroacoustic technology, there was a second evolution, that of the synthesiser: the creation of sounds from nothing, just by using electronic components. Some of the pioneers at the beginning of the 20th century included the Russian Léon Theremin, Maurice Martenot and Laurens Hammond. Finally, it took until the 1960s for the synthesiser to really break through. With thanks to Robert Moog, among others. The purpose of the synthesiser was, on the one hand, to create "new, non-existent sounds". On the other hand, they also tried to imitate acoustic instruments. Including the sound of a piano. It was not until the end of the 1970s that the first "electronic pianos" based on the principle of the synthesiser appeared on the market. The problem, however, was that the sound of a piano is so complex, and its harmonic content so diverse, that it was impossible to generate a realistic sound. Brands such as Yamaha and Roland did bring some instruments onto the market, but ultimately it was not a success. These instruments also caused a negative image of electronics and pianos among pianists. This second evolution therefore came to a standstill. It was not until 2010 that Roland surprised friend and foe with its V-piano technology: once again, a piano sound is generated "out of nowhere". But this time it is extremely realistic, via Virtual Modelling. But even pure virtual modelling is not appreciated by everyone. Because of its mathematical correctness, it is often experienced as cold and unnatural.

A third evolution was that of "sampling" or the recording and reproduction of the original piano sound. The first instruments that could do this were the Mellotron and the Chamberlain in the 1960s and 1970s. Put simply, for each note there was a recording on magnetic tape of, say, a piano sound. When the key was pressed, the tape played the sound. When the key was released, the tape was brought back to its starting position. Needless to say, this principle did not work for playing Rachmaninov! When the "magnetic tape" was gradually replaced by the digital recording (sampling), this idea could again be put into practice. The first "samplers" cost tens of thousands of euros and were only a (financial) option for the big recording studios and big artists. Think of the Synclavier, which Stevie Wonder was so fond of. For every other sound, a lot of large floppy disks had to be loaded.

But with the advent of better and faster computers, and computer memory becoming ever cheaper, the principle of sampling could finally be commercialised in the second half of the 1980s. In 1984, Kurzweil's K250 was the first instrument to offer a piano sample stored in ROM memory.

Closer to home, the German company Wersi Electronics developed a technique for processing and compressing the various string resonances and the typical harmonic changes at each stroke via ASIC technology. These developments formed the basis on which large Japanese and American corporations could develop further. And it is on these developments that virtually all digital pianos are based today. Computer memory is becoming cheaper and faster, more and more samples can be recorded per key, and various side effects are added. All this results in an ever-improving imitation of the piano sound. But ultimately, the original remains unequalled, which is why the acoustic piano and grand piano have not lost any of their importance and interest, even in the 21st century.

Do you want to know why digital pianos are so popular? Read the blog "Why you should (not) go for a digital piano", and you are all up to date!